Lessons from the Field

Lessons from the Field

There is broad agreement in the United States that we need to increase broadband coverage and make broadband more affordable for low income Americans. To arrive to that conclusion, it is unnecessary and actually is counter-productive to use less than reliable data to make this point.

Thomas Philippon recently authored a paper entitled, “How Expensive are U.S. Broadband and Wireless Services.” In it he concludes the American consumers pay more for broadband and wireless services than consumers in other industrialized nations. Unfortunately, these conclusions appear to be based on data that are dated, incorrect, omitted or misinterpreted. The findings are actually a disservice to the goal of closing the digital divide that exists both in coverage and affordability.

Fixed broadband prices

To compare U.S. with European prices, the paper uses data collected by cable.co.uk, an advertising website in the UK that tries to convince UK customers to buy UK broadband services rather than relying on unbiased sources. It is not clear what expertise this company has at determining U.S. broadband prices (or interest in showing them to be economical) and conducting proper apples-to-apples international price comparisons. In particular, there are no data contained within cable.co.uk’s currently provided spreadsheet that allow a reviewer to ascertain that similar quality plans were sampled in each country. Indeed, this seems in doubt as in its most recent study, cable.co.uk reports that the plans it sampled from the U.S. had an average price of $59.99, with a minimum price of $29.99 and a maximum of $299.95. The magnitude of this variation suggests that the sampled plans varied widely in quality (i.e., offered speeds), and it is especially curious that cable.Co.UK’s computed average speed should be $59.99. For an average from 26 observations to arrive at this archetypical retail price number seems improbable.

Indeed, it is highly likely that the quality of broadband services that cable.co.uk compares are quite different. In its current report on prices, cable.co.uk suggests that readers should also examine cable.co.uk’s study of worldwide broadband speeds. It is more than a little revealing that in the provided spreadsheet, cable.co.uk finds U.S. average speeds to be nearly twice as fast as UK speeds (71.20 Mbps vs. 37.82 Mbps). Furthermore, the only listed European countries or dependencies that exceed the U.S. in speed are:

- Liechtenstein (population of 38,747)

- Jersey (A British crown dependency of population of 107,800)

- Andorra (77,142 people)

- Gibraltar (a British Overseas Territory with 33,701 people),

- Luxembourg (590,667 people)

- Iceland (population 356,991),

- Switzerland (8.5 million inhabitants),

- Monaco (population of 38,964),

- Hungary, (9.7 million people)

- Netherlands (population of 17.2 million)

- Malta, (460,297 inhabitants)

- Denmark, (5.7 million people)

- Aland Islands, (Swedish-speaking semi-autonomous region of Finland of 27,929 people)

- Sweden, (10 million populations)

- Slovakia (5.4 million people).

As you can easily see someone tried really hard to increase the count of geographies that have faster speeds than the US by including parts of countries, dependencies, and dutchies into the mix. Nearly all of these are small countries or semi-autonomous regions with populations less than a typical U.S. city or state. It is notable that no European country with a population larger than that of the Netherlands makes the list of countries with faster average services than the U.S. Given that U.S. broadband speeds exceed significantly those in Europe, and the U.S. generally has much lower population densities, higher wages, and thus, significantly higher per-home network deployment costs, it is unremarkable that U.S. prices might exceed European prices as it costs substantially more to deploy these networks.

The scatterplot of cable.co.uk’s collected prices appears to be consistent with 2017 prices reported by the OECD. But four-year-old prices don’t seem terribly apposite to debates about the current price and quality performance of broadband in the U.S. As demonstrated by USTelecom, broadband prices in the U.S. have been dropping significantly over the past six years even as their service quality has increased dramatically.

After noting that “some of the data measures presented above [in the paper about pricing] are a few years old,” the paper turns his concern to USTelecom’s recent report detailing that deployment of advanced networks is further along in the U.S., and subscription to these high speed U.S. networks exceeds European subscription to similar networks. The paper retort to these findings, that derive directly from data and official statistics collected for the U.S. by the FCC, and for Europe by the European Commission (EC)is to reference a 247-slide presentation published on internet that claims that in 2019, 87% percent of people in the U.S. use the internet, but in Western Europe and Northern Europe, the figures are 92% and 95%, respectively.[1]

There are at least two problems with this response. First, even if these data were valid, they focus on geographic subsections.[2] Why not compare these most-developed areas of Europe against U.S. figures strictly for the Northeast or the Pacific Coast? But aside from needing to slice and dice European data in order to adduce a favorable comparison, the biggest problem is that even if Europeans are using the internet, EC DESI data on connectivity show that many are not using it via a fixed broadband connection. This is because the EC finds that only 78% of European households subscribed to fixed broadband in 2019. So it is more than likely that the slide presentation the paper cites to on usage includes people who use the internet via mobile wireless broadband connections, satellite connections and dial-up internet connections, in addition to fixed line broadband connections.[3] In any event, one year earlier, in 2018, 84% of U.S. households had fixed broadband subscriptions – and the U.S. advantage over Europe widens as only 30+ Mbps broadband speeds and 100+ Mbps speeds are considered.

Fixed broadband speeds

The next topic specifically addressed by the paper is fixed broadband connection speeds. For this, the paper refers to slide 52 in the 247-slide presentation. This slide, he says, “shows the US is close to the EU median, and slightly below France, in terms of speed.” The first statement appears to be false, the second is immaterial. Let’s unpack.

The European countries listed (in terms of speed) on the slide are: Romania, Switzerland, France, Sweden, Spain, Denmark, Netherlands, Portugal, Poland, Belgium, Germany, Ireland, U.K., Italy and Austria.[4] The U.S.A. slots between Sweden and Spain. Now even assuming that the paper meant these comparisons to be against European countries rather than EU countries as he states in the paper, the median European country is Portugal – which lies four positions below the U.S. If only EU countries are considered, the median position drops another half slot to be between Portugal and Poland.[5] While the paper may consider the U.S.’ positioning in these lists to be “close” to the median, he could also have noted that the only major EU country ahead of the U.S. was France, with a miniscule (and likely statistically meaningless) speed advantage of 500 Kbps (131.3 Mbps for France versus 130.8 Mbps for the U.S.).

Thus, rather than showing the U.S. to be a laggard in fixed broadband speeds, the paper’s analysis appears to show it significantly in the lead.

Lightning round

ARPU: The paper then claims to look at broadband ARPU for Altice and Comcast in the U.S., and pronounces it significantly above that in France. The validity of his data is highly questionable, though. For example, Philippon claims (without citation) that Altice’s ARPU is $90/month.[6] Reference to Altice’s SEC 10-K report (at p. 3) indicates that its residential broadband ARPU is $70.52, a figure substantially less than Philippon’s unreferenced figure of $90. Further, Altice is a cable company with a very substantial FTTH footprint. It reports that the average speed purchased by its customers exceeds 300 Mbps – over twice the average speed experienced by French customers.

Prices of comparable contracts: A chart is displayed suggesting that prices for triple-play services in the U.S. exceed significantly those in European countries. This statistic is likely meaningless because it is well known that the cost of television services in U.S. triple-plays is vastly above similar charges in Europe. This is due to many factors, including: U.S. bundles typically include many more channels, especially HD channels, than European bundles; fees paid by U.S. triple-play operators to acquire local broadcast channels, sports channels and other cable television networks exceed greatly those paid in Europe. Indeed, in many European countries, local broadcast channels are paid for via television license fees that are paid separately by customers and are not included in their triple-play bills; U.S. bundles also commonly allow the subscriber to watch several simultaneous programs on multiple television sets – in contrast to European bundles that may be restricted to a single TV set stream.

Labor cost adjustment: Here the paper argues that because “wages are about 20% higher in America than in the main EU countries” and “since compensation of employees accounts for half of the value added in private industries, one might expect [U.S.] price to be [only] 10% higher” than in Europe. This analysis is not compelling. Even if these national-level statistics are specifically applicable to the U.S. broadband industry, there is no need for wage differences to account for the entire amount of any putative elevation in U.S. broadband prices over European ones. That is, they are only a contributor. The fact that the U.S. is much less densely populated than Europe and U.S. networks provide much higher speeds and carry much more data per household than European ones are also likely contributors.

Profits and investment: This section contains a mishmash of data that purport to suggest that U.S. capital investment is not impressive. But, the data presented for “Comcast, AT&T, and other Telecom companies,” not an appropriate basis for analysis because many of these companies are diversified into businesses other than broadband. Comcast and AT&T offer television services and own movie studios. Comcast owns theme parks and AT&T owns legacy copper telephone networks and DBS satellite systems. Consolidated capex figures from these companies are inadequate to discern broadband-specific investments.

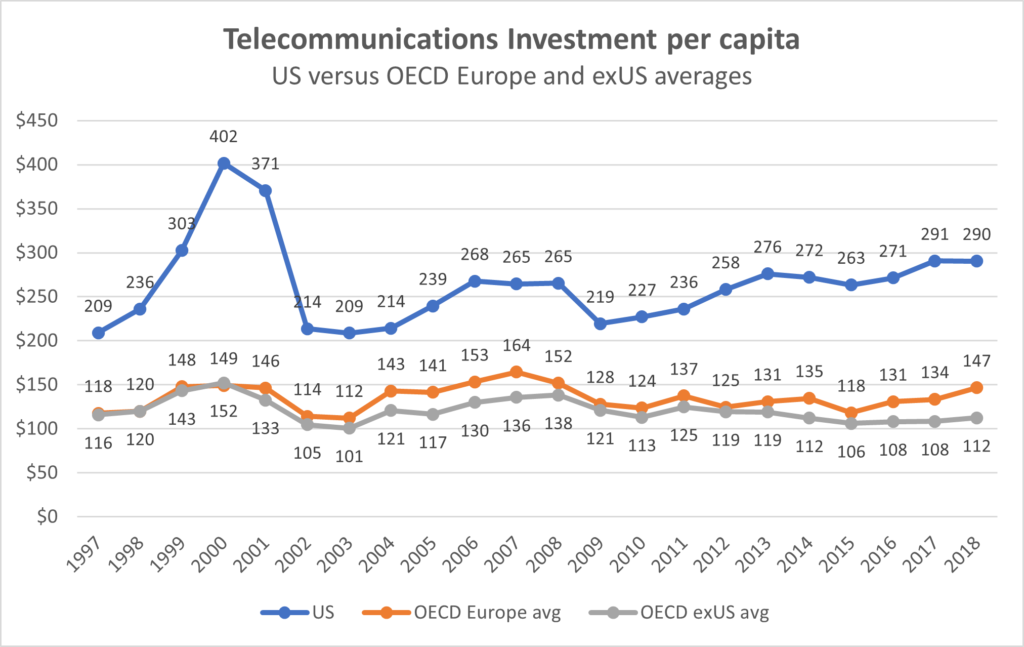

But in any event, discussion of the above is probably intended to divert attention away from the best available investment comparator for telecommunications, the data collected by the OECD from national statistical agencies or regulators.[7]

Sources: Investment data extracted from: OECD, “Telecommunications database”, OECD Telecommunications and Internet Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00170-en; OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, Table 3.10 https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/deo2017data/Table%203.10.%20Investment.xls; OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2015, Table 2.26 https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/deo2015data/2.26-Investment.xls and Table 2.31 https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/deo2015data/2.31-InvestCapita.xls. Population data extracted from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ALFS_POP_VITAL# .

All that the paper appears to say in response to the investment history presented in above chart is to note that since 2015, “investment by the main Telecom operators in Europe has grown rather quickly.” So it has; but so has investment grown in the U.S. – and U.S. per capita investment levels remain at nearly twice those in Europe.

Coda

It is odd that the paper should resort to such a strange mix of data that are old, wrong, or misinterpreted to try to support his claim that U.S. broadband is too expensive, and that this can only be the result of a lack of competition. Only by ignoring the fact that broadband networks are more widely deployed in the U.S. than in Europe, offer higher speeds, carry more data, and are more heavily subscribed to can the paper conclude that the European model is to be preferred. But while that may be the paper’s conclusion, it is not that of the European Commission which has studied these issues directly. In Table 7 of Annex 3 in its International Digital Economy and Society Index specifically for connectivity finds the U.S. to score higher than all but the top EU country (Denmark) and to tie in score with the next two highest EU countries (Finland and Malta).[8] All other EU countries score lower.

So the real truth is that U.S. fixed broadband leads, and does not lag Europe’s performance. This does not take away that there are Americans that cannot get broadband internet or cannot afford broadband. We need to help these people and do not need to trump up the differences to come to that conclusion.

[1] Curiously, the paper ascribes his data source’s stated figure of 87% usage for North America to be the usage figure specific to the U.S. This, of course, neglects the fact that roughly 10% of North America’s inhabitants are Canadians.

[2] The sources cited for this agglomeration of statistics (slide 34 of 247) are not traceable. They include: ITU, Global Web Index, GSMA Intelligence, Eurostat, Social Media Platforms’ Self-Service Advertising Tools, Local Government Bodies and Regulatory Authorities, APJ۩, and United Nations. Indeed, this same boilerplate list of sources appears on several other slides in the presentation.

[3] Indeed, reference to the Eurostat household questionnaire that appears to be the ultimate source for the paper’s cited statistics confirms that wireless broadband, satellite and dial-up are included in the European usage figures. See, ICT usage in households and by individuals (isoc_i) (europa.eu) and https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/919a2bf9-d2e0-4d00-8c72-ddcee7f3285a/MQ_2020_ICT_HH_IND.pdf.

[4] Turkey (which is below Austria in speed) is possibly another European country on the slide, but out of conservatism, we will not include it in our analysis.

[5] The EU countries contained in the slide’s list are: Romania, France, Sweden, Spain, Denmark, Netherlands, Portugal, Poland, Belgium, Germany, Ireland, U.K., Italy and Austria. Switzerland in not an EU country. Note that the U.K. was still a member of the EU when these data were collected.

[6] We assume this is intended to be residential ARPU because the paper compares it against a French statistic for residential broadband prices.

[7] OECD Telecommunications and Internet Statistics, http://www.oecd.org/sti/broadband/9b.Investment.xls and https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EDU_DEM.

[8] Connectivity dimensions are defined as: Fixed Broadband Coverage, Fixed Broadband Take-up, 4G Coverage, Mobile Broadband Take-up, Fixed Wired Broadband Speed and Broadband Price Index.