Wouldn’t it be nice if everything worked together like magic? Well, while wireless seems like magic to us, it is pure physics that make it work. Wishful thinking, ideological dictums, and philosophical preferences have no effect on how it actually works. On top of that, trying to make everyone happy usually results in making nobody happy.

The 700 MHz band is a mess created by the pursuit of a regulatory fantasy, aggravated by an artificial deadline provided by law, and compounded by the desire to please everyone and hurt nobody.

The combination of clean spectrum with highly encumbered spectrum that TV stations still use to broadcast, spectrum that comes with net neutrality and private-public partnership rules attached, and broadcast-only spectrum has been a disaster. The broadcast winner invested billions only to realize that there is no demand for broadcast TV the way they did it and therefore had to sell that spectrum. The net neutrality spectrum owner is currently in court to get the neutrality removed. The public-private partnership never happened because the private investors that were supposed to finance the network never showed up because of the onerous terms that the FCC imposed. The owners of the encumbered spectrum demand interoperability from the folks that deliberately bought clean spectrum to avoid the interference problems the encumbered owners are facing.

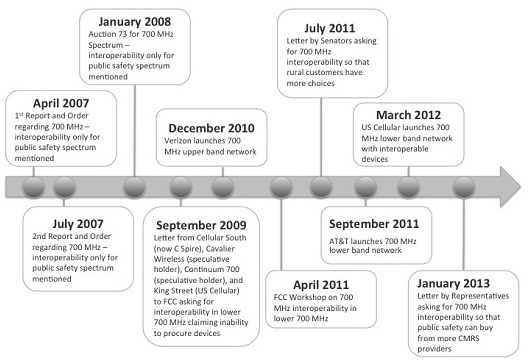

The encumbered/clean spectrum fight is the most fascinating one. It should come as no surprise that there was a significant difference in price for the spectrum: One has no problems, the other has significant interference issues; one was expensive to purchase, the other one was cheap. The ITU, which has a global perspective, looked at the issue and created a new band that separated the two. Many of the winners of the cheap, problematic A-Block cry foul and want the buyers of clean B-Block to put the same electronics in their phones as A-Block owners do, even though the winners of the B-Block do not own A-Block spectrum–and all of that in the name of competition. This is an unprecedented step because never before has there been a required interoperability between bands in the United States. The A-Block winners, many of them small operators, claim that AT&T, the largest winner of B-Block licenses, is effectively prohibiting them from providing service and force them to leave their spectrum idle and worthless. What is quite interesting is that even though U.S. Cellular complained in a letter to the FCC in December of 2009 that it would be left without equipment options and that there would be no coverage in rural America unless the FCC would mandate interoperability. Barely six months after AT&T, U.S. Cellular launched its 4G LTE on its A- and B-Block wireless licenses with blockbuster devices like the Samsung Galaxy S III. If it can do it, why can’t the others? This shows that any government-mandated technical solution is unnecessary and would be misguided. The right approach to fixing the problem is to fix the source of the problem–the relocation of the TV stations operating on Channel 51 that everyone knew would create problems. The alternative of forcing interoperability is just shifting the cost to consumers, of which more than 90 percent will never need the solution interoperability wants to fix.

Furthermore, in no other spectrum band, with the exception of cellular band with the very first cellular systems in the early 1980s, is anyone required to interoperate, but since then such interoperability has only be undertaken when it was opportune for the spectrum owner. For example, T-Mobile USA sells devices that only work on the PCS spectrum not the cellular spectrum, because for a long time T-Mobile USA only owned PCS spectrum. AT&T’s devices work on both cellular and PCS because it owns spectrum in both bands. Applying the same logic that the A-Band owners are using, T-Mobile would have to be interoperable with cellular even though the T-Mobile customers will never use the cellular band. The repercussions of requiring interoperability would have to be universal and would be extremely expensive for consumers with minimal if nonexistent benefits.

In any case, the FCC should not have sold impaired spectrum while it was hawking four different classes of spectrum in the same auction. There were simply too many balls in the air and it created an unrealistic expectation that the spectrum somehow would be the same. To aggravate the situation, the FCC didn’t proactively propose a solution, but instead just stepped away from the mess. In the future, the FCC could avoid further disasters like the 700 MHz auctions by only selling the same type of spectrum with the same properties and impairments. It is better for an entire auction to fail and then be redone the right way later on than to suffer through a hodgepodge of rules and parts that fall short, like with the 700 MHz auction. The current outcome is depriving consumers and business alike–justified or not–from the use of valuable spectrum that helps to propel our economy forward and delights consumers with lightning-fast data services.