In our previous report, we established that policymakers must choose among competing outcomes when the agency makes spectrum allocation decisions, including the number of licenses the agency wants to award, the cost to build out the licenses, and network speeds based on channelization. In light of the FCC’s recent decisions in the AWS-3 and incentive auction proceedings, the agency appears to have decided that more narrow spectrum channels, allocated across smaller geographic areas, is the preferred outcome. Europe, on the other hand, has opted to allocate spectrum in wider channels. This note attempts to analyze whether the FCC’s spectrum allocation choices will put US wireless carriers at a disadvantage when it comes to the speed of their networks, as compared to providers in other countries using wider channelizations.

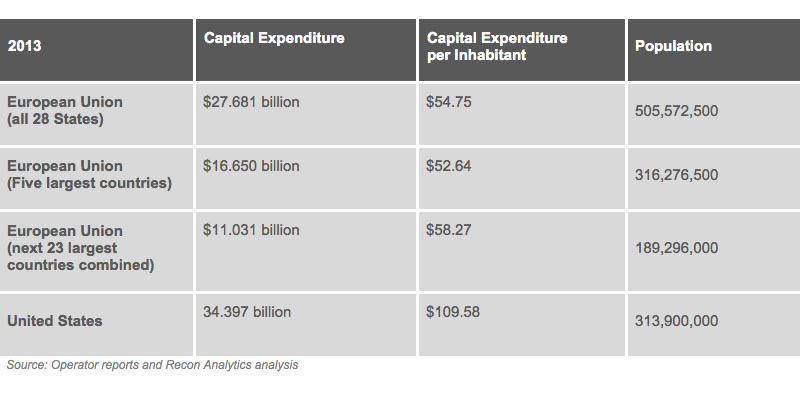

In 2013, US wireless capital expenditure spending hit an all-time high. AT&T’s attempt to overtake Verizon in network quality had the company spending roughly $11.5 billion on network improvements, while Verizon Wireless spent another $9.75 billion improving its network. Let me put this into context: AT&T and Verizon together spent more money improving their networks in 2013 than all 20 operators serving the five largest EU countries (EU5) combined. Once we add the capital expenditure of Sprint and T-Mobile, which both spent more on network improvements last year than they had in previous years, US operators spent more than twice as much as the EU5 operators did to improve their infrastructure covering roughly the same number of subscribers. Even when adding all 98 operators active in the EU together, their combined capital expenditures are only 80% of what the US operators are investing.

Indeed, US wireless carriers spent roughly $109.58 per US citizen to upgrade wireless infrastructure in 2013 whereas the EU5 carriers that serve the more affluent European countries spent significantly less, at roughly $52.64 per citizen. Whether you look at the investment numbers on their own or in comparison with what non-US wireless companies are spending, America’s wireless companies appear to be at the upper bounds of investing in infrastructure. Why is this an important point? Current reports and research indicate that the cost to build out wide area mobile networks using more narrow channelizations is a more expensive proposition than building out wider channels as illustrated in Peter Rysavy’s Mobile Broadband Explosion white paper.

So, with US wireless carriers at the upper bounds of investing in infrastructure, is it reasonable to assume that they will spend even more money to deploy small channel networks that are slower and less efficient? Most investors will tell you that that is not a tenable outcome.

So what does this mean? In the US, the carriers that have the largest swaths of contiguous spectrum will be able to provide fast download speeds. Only Sprint is continuously in this fortuitous situation and in some markets T-Mobile, due to pure happenstances, also has 20×20 MHz contiguous spectrum. The other carriers will have to rely on costly and still unproven “carrier aggregation technology” to achieve results similar to what is possible with wider, contiguous spectrum blocks. The big question, then, is what the additional overhead will be to make it a reality and deploy it extensively. None of the vendors working on carrier aggregation technology are willing to publically state how much the overhead will be. That’s not a good omen. Compounding the issue is the fact that the appetite for carrier aggregation technologies has waned because European carriers have moved to wider channelizations, receiving 20×20 MHz licenses in their last spectrum auctions. Thus, the European operators do not need carrier aggregation technology for the foreseeable future, alleviating the pressure on vendors to quickly develop the standards and related equipment. That might explain why the vendors have quietly extended the timeline for when US carriers will be able to use two and three channel carrier aggregation.

Although it is doubtful the FCC intended to retard the proliferation of high speed wireless broadband networks when it made some of its more recent spectrum allocation decisions, the agency may have inadvertently created an environment where this very result will occur. The simple laws of physics (smaller spectrum channels + (higher traffic volumes * more users) = slower network speeds) combined with economic realities (US companies are already at the upper bounds of capital expenditures to build out wireless networks) portend a slower future for America’s wireless subscribers.