The U.S. wireless industry has officially entered a new era, catalyzed by a landmark transaction that confirms the final collapse of EchoStar’s long-held ambition to become a fourth facilities-based carrier. EchoStar has entered into a definitive agreement to sell its complete portfolio of prized AWS-4 and H-block spectrum licenses to SpaceX for approximately $17 billion. The deal, consisting of up to $8.5 billion in cash and an equivalent amount in SpaceX stock, also includes a provision for SpaceX to fund approximately $2 billion of EchoStar’s debt interest payments through late 2027 and establishes a long-term commercial agreement for SpaceX to provide its next-generation Starlink Direct-to-Cell (D2C) service to EchoStar’s Boost Mobile subscribers.

This agreement is not merely a corporate restructuring; it is the definitive end of a regulatory dream and the formal beginning of a new, more complex competitive paradigm. The transaction solidifies the U.S. terrestrial wireless market as a stable, three-player market while simultaneously igniting a new, asymmetric competitive front in satellite-to-cellular connectivity. SpaceX, now armed with dedicated, purpose-built spectrum for Mobile Satellite Service (MSS), and its primary terrestrial partner, T-Mobile, possess a significant first-mover advantage in the race for ubiquitous coverage. This move elevates the D2C value proposition from a niche, emergency-only feature into a core, marketable network attribute.

The cascading effects of this deal will reshape the strategies of every major player for years to come. For EchoStar, it marks the final pivot from a would-be network operator to a “hybrid MVNO” and a significant shareholder in SpaceX, a stunning financial victory for its chairman, Charlie Ergen, born from the ashes of operational failure. For Verizon and AT&T, it provides urgency to accelerate their own D2C counter-strategy with partner AST SpaceMobile. Finally, the transaction presents a novel challenge for regulators. The review will be forced to look beyond traditional concerns of terrestrial spectrum consolidation and grapple with the profound implications of SpaceX’s vertical integration, examining its dominance in the satellite launch market and its new, powerful position in the downstream market for satellite connectivity services. The two-front war has begun.

I. The Deal That Ends an Era: Deconstructing the EchoStar-SpaceX Agreement

The definitive agreement between EchoStar and SpaceX represents one of the most significant strategic transactions in the recent history of the U.S. telecommunications sector. Its architecture reflects the unique financial positions and strategic imperatives of both companies, transferring a uniquely valuable set of spectrum assets that will power a new generation of satellite services and formalizing a commercial alliance that provides a lifeline to a struggling wireless brand.

Financial Architecture and Valuation Analysis

The transaction is structured to provide EchoStar with immediate financial relief and long-term upside, while allowing SpaceX to acquire a critical strategic asset without depleting its capital reserves needed for its ambitious launch and satellite manufacturing programs. The core terms of the agreement are as follows :

- Total Consideration: The deal is valued at approximately $17 billion.

- Cash Component: SpaceX will provide up to $8.5 billion in cash.

- Stock Component: SpaceX will provide up to $8.5 billion in its own stock, with the valuation fixed as of the date the definitive agreement was signed.

- Debt Servicing: In a crucial provision that addresses EchoStar’s immediate liquidity crisis, SpaceX has agreed to fund an aggregate of approximately $2 billion in cash interest payments due on EchoStar’s substantial debt through November 2027.

This 50/50 cash-and-stock structure is a work of strategic financial engineering. A pure cash deal of this magnitude would place immense strain on SpaceX, a company with massive and continuous capital expenditures for its Starship development and Starlink constellation deployment. Conversely, a pure stock deal would have been unacceptable to EchoStar’s creditors, who require cash to service the company’s more than $26.4 billion in total debt. The balanced split provides an elegant solution. SpaceX preserves vital capital for its core operations, while EchoStar secures sufficient immediate liquidity to manage its most pressing debt obligations and stabilize its financial footing.

Furthermore, by accepting a significant equity stake in one of the world’s most valuable private companies, EchoStar Chairman Charlie Ergen has transformed what could have been a simple liquidation of assets into a long-term investment. This move aligns the financial interests of both parties in the success of the D2C venture that this very spectrum will empower. It gives EchoStar and its shareholders continued participation and upside potential in the high-growth satellite connectivity ecosystem, effectively hedging the sale of its own ambitions against the success of its acquirer.

Asset Deep Dive: The Strategic Value of AWS-4 and H-Block Spectrum

The intense pursuit of these specific licenses by SpaceX was driven by the unique and irreplaceable nature of the AWS-4 band. While the H-block licenses are a valuable addition, the AWS-4 spectrum—encompassing the 2000-2020 MHz uplink and 2180-2200 MHz downlink bands—is widely considered the “golden band” for D2C services.

Its value stems from its history and technical characteristics. Unlike repurposed terrestrial spectrum, such as the sliver of T-Mobile’s PCS G-block currently used for the beta T-Satellite service, the AWS-4 band was originally allocated for Mobile Satellite Service (MSS). The propagation physics of both bands are ideal for the challenges of space-to-ground communication, making it far more efficient for connecting satellites to standard smartphones. More importantly, its existing regulatory framework as an MSS band provides a more direct and less contentious path for satellite use, sidestepping many of the complex technical and legal challenges associated with using terrestrial-designated bands from space under the FCC’s new Supplemental Coverage from Space (SCS) framework.

By acquiring the entire portfolio of these licenses, SpaceX secures exclusive, nationwide rights to this optimal spectrum. This acquisition is transformative, enabling SpaceX to develop and deploy a next-generation Starlink D2C constellation capable of moving beyond the limitations of the current text-only service. With dedicated, purpose-built spectrum, SpaceX can now credibly pursue its roadmap of offering reliable voice, streaming-grade data, and robust IoT capabilities directly to unmodified smartphones, a quantum leap in service capability.

The Commercial Alliance: Defining the Future of Boost Mobile and Starlink D2C

A core component of the definitive agreement is the establishment of a long-term commercial alliance. This partnership will enable EchoStar’s Boost Mobile subscribers to access SpaceX’s next-generation Starlink D2C service, with the connection being managed through Boost’s own cloud-native 5G core network. While seemingly a straightforward value-add for customers, this commercial agreement serves multiple, layered strategic purposes for both companies and for the deal’s regulatory prospects.

For EchoStar, the alliance provides a desperately needed lifeline and a unique point of differentiation for its struggling Boost Mobile brand. Facing relentless subscriber losses and the decommissioning of its own physical network, Boost can now market a truly innovative feature—ubiquitous satellite connectivity—to stanch churn and potentially attract new customers in the hyper-competitive prepaid market. It allows EchoStar to maintain a narrative of being a technology-forward competitor even as it fully transitions to a “hybrid MVNO” model, reliant on the networks of its rivals. It still does not solve Boost Mobile’s remarkable inability to sell its services successfully.

Most critically, this commercial component is a masterful piece of regulatory strategy. The preservation of Boost Mobile as a distinct competitive entity, now enhanced with a unique satellite offering, provides essential political cover for the transaction. It allows the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to approve a deal that otherwise permanently cements a three-player terrestrial market. Regulators can plausibly argue that they have preserved a “fourth wireless competitor,” even if that competitor no longer owns a radio access network. This framework directly mirrors the “hybrid MNO” model established in EchoStar’s prior spectrum sale to AT&T, creating a consistent and defensible regulatory precedent that will ease the path to approval.

II. EchoStar’s Final Chapter: From Contender to Catalyst

The sale of EchoStar’s most valuable spectrum assets was not a strategic choice but an inevitability, the culmination of years of financial strain, commercial missteps, and overwhelming regulatory pressure. The company’s journey from a government-mandated fourth carrier to a motivated spectrum broker is a stark cautionary tale about the brutal economics of the modern wireless industry. Yet, for its chairman, it represents the profitable conclusion to a decades-long speculative bet.

Anatomy of a Forced Sale: Financial Distress, Network Failure, and Regulatory Pressure

The fire sale of EchoStar’s spectrum was precipitated by a combination of three fatal blows that left the company with no viable path forward other than liquidation.

First, the company’s financial position had become untenable. Saddled with a total debt load exceeding $26.4 billion, EchoStar reported a net loss of $306 million in the second quarter of 2025 alone. The financial distress grew so acute that the company began missing multi-million dollar interest payments, a clear signal of a looming liquidity crisis. The post-pandemic rise in interest rates had closed the window for the cheap financing necessary to fund a nationwide network buildout, leaving the company hemorrhaging cash from its wireless division and presiding over a legacy pay-TV business in secular decline. The inclusion of a $2 billion interest payment provision by SpaceX in the final deal underscores the severity of this financial pressure.

Second, EchoStar’s flagship strategic initiative, a technologically advanced, greenfield 5G Open RAN network, was a commercial catastrophe. Despite earning technical praise for its rapid deployment, the network failed to attract a critical mass of subscribers, becoming a “ghost town” that generated no meaningful revenue or positive cash flow. This failure proved that simply building a network is not synonymous with building a successful wireless business. The surrender was signaled definitively when the company laid off 90% of its wireless engineering organization following its initial spectrum sale to AT&T, an irreversible move away from any serious network ambitions.

Finally, the FCC, under Chairman Brendan Carr, delivered the coup de grâce. Prompted by public questions from Elon Musk about why EchoStar was allowed to hold valuable spectrum without fully utilizing it, the commission launched a high-profile campaign against the company’s “spectrum squatting”. This regulatory pressure, amplified by relentless lobbying from SpaceX, initiated formal inquiries into EchoStar’s buildout compliance and effectively froze the company’s ability to raise capital. Cornered financially and regulatorily, Chairman Charlie Ergen was forced to abandon his decades-long strategy of hoarding spectrum, leaving a sale as his only remaining option. Both the AT&T and SpaceX deals are explicitly framed by EchoStar as necessary steps to resolve these pending FCC inquiries.

The Definitive Pivot: Termination of the MDA Space Contract

If any doubt remained about EchoStar’s complete and total surrender of its network infrastructure ambitions, it was erased by a single, decisive action that occurred concurrently with the SpaceX deal announcement. On September 8, 2025, EchoStar issued a termination for convenience notice to MDA Space for a major satellite constellation contract that had been announced just five weeks prior, on August 1, 2025.

This sequence of events reveals the stark, binary choice the company faced. The initial MDA Space contract was a bold statement of intent, committing EchoStar to a multi-billion dollar project to build its own Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite constellation for D2D services, positioning itself as a direct competitor to Starlink. It was the “build” path. The subsequent termination, explicitly cited as the result of a “sudden change to EchoStar’s business strategy and plan in the wake of spectrum allocation discussions with the Federal Communications Commission,” was the definitive pivot to the “sell” path. This was not a gradual strategic evolution but an abrupt reversal. The deal with SpaceX made building its own constellation both unnecessary and impossible. The termination of the MDA contract is the final, irrefutable evidence that EchoStar has permanently exited the network infrastructure business, both on the ground and in space.

The Financial Epilogue for Ergen: A Masterclass in Spectrum Arbitrage

Despite the spectacular operational failure of the fourth-carrier project, the great spectrum reshuffle represents an immense financial victory for Charlie Ergen. Over several decades, he masterfully acquired a vast portfolio of spectrum licenses, often at prices far below today’s market value. The recent sales are the culmination of this long-term arbitrage strategy.

The August 2025 sale of 600 MHz and 3.45 GHz spectrum to AT&T netted approximately $23 billion, a price tag roughly $9 billion higher than what EchoStar originally paid for those licenses. Combined with the approximately $17 billion transaction with SpaceX, the total proceeds from the spectrum liquidation will be around $40 billion. This sum is more than sufficient to retire EchoStar’s entire $26.4 billion debt load, with a substantial multi-billion dollar profit remaining for Ergen and the company’s shareholders. While his dream of being a wireless network king is dead, the poker player has walked away from the table with the jackpot.

III. Starlink’s Quantum Leap: Forging a New Satellite-Terrestrial Paradigm

The acquisition of EchoStar’s AWS-4 and H-block spectrum is a watershed moment for SpaceX. It catapults the company’s Starlink division from a promising but niche player in the D2C space into a position of formidable power, armed with the ideal assets to realize its global ambitions. This deal fundamentally alters the D2C value chain, supercharges its alliance with T-Mobile, and introduces complex new questions of vertical integration for antitrust regulators.

From Partner to Kingmaker: The Power of Dedicated MSS Spectrum

Until now, Starlink’s D2C service, offered in partnership with T-Mobile, has been a groundbreaking but technically constrained offering. It has operated by leasing a small slice of T-Mobile’s terrestrial PCS spectrum, a band not optimized for the physics of space-to-ground communication. This has limited the service to basic text messaging, with a roadmap for voice and data still in development.

The acquisition of dedicated, nationwide MSS spectrum changes everything. As previously noted, the AWS-4 band is purpose-built for satellite communications, offering superior performance and a clearer regulatory path. Owning this “golden band” allows SpaceX to transition from a D2C partner, reliant on a carrier’s terrestrial assets, to a D2C kingmaker that controls its own destiny. With exclusive rights to this spectrum, SpaceX can now engineer a fully optimized, next-generation satellite constellation designed to deliver on the full promise of D2C: reliable voice, high-quality data streaming, and ubiquitous IoT connectivity directly to standard smartphones. This elevates the D2C value proposition from a novelty or emergency feature into a core, marketable network attribute, fundamentally changing the competitive landscape.

The T-Mobile Alliance Supercharged: Forging a “Ubiquity Moat”

The most immediate beneficiary of SpaceX’s empowerment is its primary U.S. partner, T-Mobile. The combination of T-Mobile’s extensive terrestrial 5G network and Starlink’s enhanced D2C capabilities creates a hybrid network with a profound competitive advantage. T-Mobile will soon be able to market a service that offers virtually seamless connectivity, eliminating terrestrial dead zones for core voice and data services across the vast majority of the U.S. landmass.

This capability directly addresses a primary consumer pain point and a top purchase driver: the ability to make calls and use data anywhere. This “ubiquity” feature becomes a formidable competitive moat. It creates a stickier service that could significantly reduce customer churn, particularly among high-value subscribers in rural areas, outdoor enthusiasts, and enterprise clients in sectors like logistics, agriculture, and transportation. It provides a compelling reason for customers of rival carriers to switch to T-Mobile and a powerful reason for existing customers to stay. While the service will have inherent limitations, satellite signals struggle to penetrate buildings, confining the primary use case to outdoor environments, its value in eliminating outdoor dead zones gives T-Mobile an asymmetric advantage that rivals, with their still-nascent D2C partnerships, cannot immediately match.

Antitrust Headwinds: Scrutinizing the Vertical Integration of a New Power Broker

While the transfer of spectrum licenses from a non-competitor (EchoStar) to a new entrant (SpaceX) may not trigger traditional horizontal antitrust concerns, the deal’s approval is not guaranteed. It is highly unlikely that the FCC or DOJ will put significant conditions on this deal even though it raises a more complex and potentially more problematic issue: vertical integration and the market power of SpaceX.

The structure of this transaction creates a classic vertical integration scenario that will force antitrust authorities to consider novel questions in the telecommunications space. SpaceX is already the dominant player in the upstream market for satellite launch services, controlling a vast majority of the global commercial launch market. Many of its direct competitors in the satellite communications industry, including companies building rival D2C constellations, are dependent on SpaceX’s rockets to get their satellites into orbit. This reliance has already raised concerns about SpaceX potentially favoring its own Starlink constellation.

By acquiring scarce, premium MSS spectrum, SpaceX is now poised to become the dominant player in the downstream market for D2C services in the U.S. This combination of upstream and downstream market power will compel antitrust enforcers to examine whether SpaceX could leverage its launch monopoly to harm competition in the D2C market. This could manifest in several ways consistent with a classic “raising rivals’ costs” antitrust theory, such as using discriminatory pricing for launches, prioritizing its own satellites over those of competitors, or demanding exclusionary contract terms that limit a customer’s ability to use other launch providers. This shifts the regulatory focus from the FCC’s public interest standard on spectrum utilization to the DOJ’s stricter antitrust framework concerning market power, competitive foreclosure, and the potential for a dominant firm in one market to stifle competition in an adjacent one.

IV. The Terrestrial Counteroffensive: AT&T and Verizon’s Race for Parity

While the SpaceX-EchoStar deal reshapes the satellite-cellular frontier, the battle on the terrestrial front continues unabated. For Verizon, the imperative to secure additional mid-band spectrum is now more acute than ever, though its path is complicated by legal disputes. In response to the formidable T-Mobile/Starlink alliance, Verizon and AT&T have been forced into an unprecedented defensive partnership, betting their D2C future on a single satellite provider, AST SpaceMobile.

The Strategic Imperative for AWS-3 and the Shadow of a Lawsuit

Verizon’s network has long been defined by its quality and reliability, but it faces a relative deficit in critical mid-band spectrum compared to T-Mobile’s vast 2.5 GHz holdings. AT&T’s recent $23 billion acquisition of EchoStar’s 3.45 GHz and 600 MHz spectrum threatened to widen this gap, potentially leaving Verizon in third place in the 5G capacity race.

However, this straightforward strategic move is complicated by a significant legal entanglement. EchoStar is currently suing the FCC in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit to block the rules governing the upcoming re-auction of these very AWS-3 licenses. The lawsuit stems from a decade-old issue where Dish Network (now EchoStar) defaulted on winning bids from the original 2015 auction. EchoStar is now potentially liable for any shortfall if the re-auction fails to generate at least $3.3 billion. EchoStar argues that the FCC’s updated, more restrictive auction rules for small businesses will suppress bidding, making a shortfall more likely and unfairly exposing the company to billions in penalties.

This litigation creates a strategic dilemma that directly impacts the competitive balance. The lawsuit introduces significant uncertainty around the timing and final cost of the AWS-3 spectrum, which Congress has mandated must be auctioned by June 2026. Any delay in the auction directly harms Verizon’s ability to close its mid-band capacity gap with AT&T, which has already secured and can begin deploying its new spectrum. Every month the AWS-3 spectrum remains in legal limbo is a month that Verizon’s network risks falling further behind in critical urban markets, eroding the very foundation of its premium brand and value proposition.

The AST SpaceMobile Gambit: A Unified Front Against a Common Threat

Faced with the powerful and vertically integrated T-Mobile/Starlink alliance, Verizon and AT&T have been driven to adopt an unprecedented counter-strategy: a joint, non-exclusive reliance on satellite partner AST SpaceMobile. Both carriers have signed commercial agreements with AST SpaceMobile and are providing it with access to their licensed terrestrial spectrum—primarily in the 850 MHz band—to power its D2C service.

This move represents a fundamental shift in the competitive dynamics of the U.S. wireless market. AT&T and Verizon are historically fierce, zero-sum competitors that have rarely, if ever, collaborated on a core strategic technology platform. Their decision to both partner with AST SpaceMobile, rather than each seeking an exclusive satellite partner, is a clear signal of the profound disruptive threat they perceive from Starlink. This “co-opetition” is a defensive alliance born of necessity. By pooling their spectrum resources and committing their vast subscriber bases to a single satellite platform, they can help AST SpaceMobile achieve the scale, funding, and regulatory momentum necessary to build a viable competing constellation more quickly. This strategy effectively transforms the D2C battle from a three-way free-for-all into a two-sided war between distinct technology ecosystems: the T-Mobile/Starlink bloc versus the AT&T/Verizon/AST SpaceMobile bloc.

Comparative Analysis: Starlink D2C vs. AST SpaceMobile

The two emerging satellite-cellular ecosystems are built on fundamentally different strategic and technical models.

- The Starlink Model: This is a deeply vertically integrated approach. SpaceX controls the rocket manufacturing, the launch services, the satellite constellation, and now, the dedicated MSS spectrum. This provides significant advantages in terms of cost control, deployment speed, and the ability to optimize the entire system—from satellite to spectrum to handset—for maximum performance. Its primary challenge is the immense capital required to build and maintain this integrated system.

- The AST SpaceMobile Model: This is a partnership-based approach. AST SpaceMobile relies on its carrier partners (AT&T and Verizon in the U.S.) for access to terrestrial spectrum and their subscriber bases. Its key technological differentiator is its satellite design, which features exceptionally large phased-array antennas. These massive antennas are designed to be powerful enough to connect directly with standard, unmodified smartphones using conventional terrestrial spectrum bands from hundreds of miles in orbit. This model is more capital-efficient for the satellite operator but introduces complexities in coordinating with multiple carrier partners and managing potential interference with terrestrial networks.

The race is now on to see which model can achieve scale and deliver a compelling service to consumers first. Starlink has the advantage of an existing LEO constellation and now, superior spectrum. AST SpaceMobile has the backing of two of the world’s largest carriers and a novel satellite architecture. The outcome of this technological and strategic competition will define the future of ubiquitous connectivity. Alternatively, AT&T and/or Verizon could abandon their AST SpaceMobile partnership and throw in their lot with Starlink. This might be a technically superior solution, but puts them at the mercy of Elon Musk.

V. Navigating the Regulatory Gauntlet

The final approval of the EchoStar-SpaceX spectrum transfer is not a foregone conclusion and must navigate a complex regulatory environment. However, the deal has been skillfully structured to address the primary concerns of the FCC, while the most likely challenge will come from state-level actors seeking consumer protection concessions.

The FCC’s End Game: Why Approval Is the Path of Least Resistance

The FCC is highly likely to approve the spectrum license transfer with minimal friction. The entire transaction is framed as the solution to the very problem that prompted the agency’s investigation in the first place: EchoStar’s perceived “spectrum squatting”. For years, and with increasing public pressure from figures like Chairman Carr, the FCC’s primary objective has been to see EchoStar’s underutilized spectrum put to more intensive use for the benefit of American consumers.

This deal achieves that objective in the most direct way possible. It transfers the licenses from EchoStar, a company that proved unable to deploy them effectively, to SpaceX, a well-capitalized and highly motivated entity that has publicly committed to building a next-generation satellite network on these exact frequencies. For the FCC, approving the deal is the path of least resistance; it allows the commission to declare victory in its campaign against spectrum warehousing. The preservation of Boost Mobile as a “hybrid MNO” with access to this new D2C service provides the necessary political and regulatory justification to bless the transaction.

DOJ and State AGs: The Inevitable Price of Consolidation

While the FCC’s path seems clear, the view from antitrust enforcers is more complex. The Department of Justice is unlikely to block the transaction outright. The “failing firm” doctrine, which was a key rationale in the approval of the T-Mobile/UScellular merger, applies directly to the collapse of EchoStar’s wireless ambitions. With EchoStar having effectively exited the market as a facilities-based competitor, the DOJ lacks a strong basis to argue that this specific spectrum transfer further harms terrestrial competition. The more salient antitrust questions, as noted, relate to vertical integration, which may result in behavioral remedies or oversight rather than a full blockade.

The most probable challenge will emerge from a multi-state coalition of Attorneys General, particularly from Democratic-led states. This is the same playbook used during the T-Mobile/Sprint merger, where state AGs filed suit to block the deal on consumer protection grounds, arguing it would reduce competition and raise prices. A similar legal challenge is almost inevitable. The AGs will argue that allowing the last major independent block of mid-band spectrum to be absorbed into an ecosystem controlled by one of the top three carriers’ partners permanently cements a three-player oligopoly to the detriment of consumers.

However, the most likely outcome of such a challenge is not a complete blockade but a negotiated settlement. Precedent suggests that the carriers will be forced to the negotiating table to offer tangible consumer concessions in exchange for the AGs dropping their lawsuit. These concessions could include multi-year price locks for low-income plans, specific buildout commitments for the D2C service in underserved rural areas within their states, and robust protections for independent Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs) to ensure a competitive wholesale market. The deal will proceed, but not without a price.

VI. Conclusion: Winners, Losers, and the Future Trajectory of U.S. Connectivity

The great spectrum reshuffle, culminating in the EchoStar-SpaceX transaction, has irrevocably altered the competitive landscape of the U.S. telecommunications and satellite industries. It has created clear winners and losers, solidified a new market structure, and set the strategic trajectories for every major player for the remainder of the decade.

Scoring the Reshuffle:

The definitive terms of the recent deals allow for a clear assessment of the strategic outcomes for all involved parties.

- Biggest Winners: The clearest victors are Charlie Ergen and SpaceX. Ergen successfully monetized decades of spectrum speculation for a massive profit, deftly navigating operational failure to achieve a stunning financial success. SpaceX acquires the “golden band” of MSS spectrum, the single most critical and previously unobtainable asset needed to realize its global D2C ambitions and establish a commanding technological lead.

- Primary Beneficiary: T-Mobile emerges as the primary strategic beneficiary among the mobile network operators. Its exclusive partnership with a newly empowered Starlink provides it with a powerful and asymmetric “ubiquity moat”—a unique value proposition of near-total coverage that will be a potent tool for customer acquisition and retention in the years to come.

- Forced to React: Verizon and AT&T are now firmly on the defensive in the new D2C battle. While their terrestrial network positions are solidified—particularly AT&T’s after its own spectrum purchase from EchoStar—they have been forced into a reactive alliance with AST SpaceMobile to counter the first-mover advantage of the T-Mobile/Starlink bloc. Their success now depends heavily on the execution of a third-party partner in a race where they are starting from behind or they might join the Starlink camp under the premise of “If you can’t beat them, join them.”

- Biggest Losers: The most significant casualty is the concept of a fourth facilities-based U.S. wireless carrier. The collapse of EchoStar’s effort, despite government mandates and access to spectrum, proves that the economic and competitive barriers to entry are now insurmountably high. EchoStar, the company, also fits this category. While financially solvent, its grand ambitions are dead. It survives as a shell of its former aspirations, relegated to the role of a hybrid MVNO presiding over a satellite TV business in terminal decline.

The Evolving Battlefield: Key Milestones and Strategic Outlook for 2026-2028

The U.S. wireless market now revolves around three titans engaged in a two-front war. The coming years will be defined by their execution on both the terrestrial and satellite fronts. The key milestones that will determine the future trajectory of the industry include:

- The timeline and outcome of the regulatory review for the SpaceX/EchoStar transaction, including any potential concessions demanded by State Attorneys General.

- The resolution of EchoStar’s lawsuit against the FCC and the subsequent timing and results of the AWS-3 spectrum re-auction, which will be critical for Verizon’s 5G capacity strategy.

- The initial commercial launch and real-world performance of Starlink’s enhanced D2C service operating on the AWS-4 spectrum, which will be the first major test of the technology at scale.

- The successful launch and operational performance of AST SpaceMobile’s first block of commercial BlueBird satellites, which will determine the viability of the AT&T/Verizon counter-strategy.

- The marketing, pricing, and consumer adoption rates of the competing D2C offerings, which will ultimately reveal whether ubiquitous connectivity is a niche feature or a mass-market demand driver that can reshape carrier loyalty.

The era of four-player competition is definitively over. The war for the future of American connectivity—a war fought simultaneously on the ground and from orbit—has just begun.

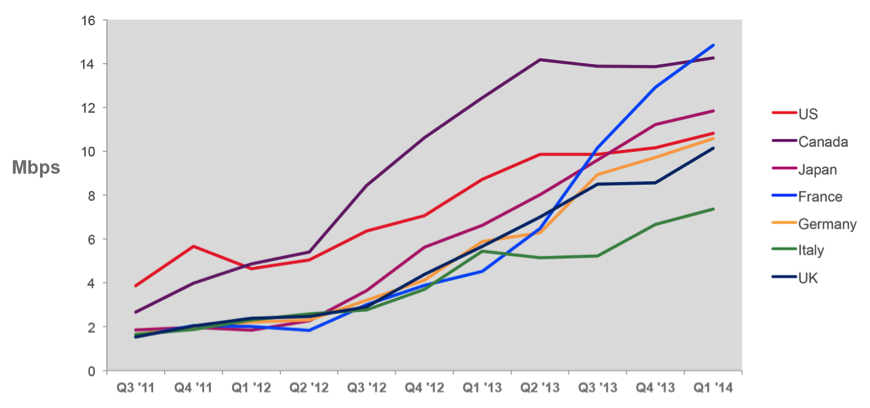

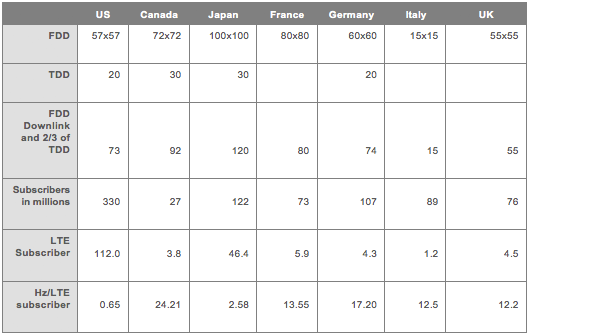

Source: Recon Analytics and Q1 2014 operator reports, 2014

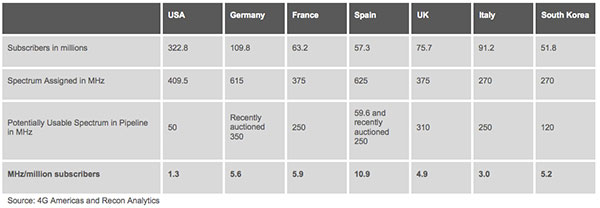

Source: Recon Analytics and Q1 2014 operator reports, 2014 As one can see in the table above, United States mobile operators are facing a significantly more constrained supply of spectrum suitable to support wireless data as compared to their foreign counterparts. When we normalize the spectrum available per person, the United States consumer is by far in the worst position. It has per person, only 1/3 of the spectrum available than Italy where demand for wireless data is comparatively weak. Other countries have assigned three to eight times as much spectrum per person to satisfy the demand for data. Consider the impact on service prices if the FCC really opened up the spectrum spigot. When spectrum was still plentiful in the United States, the wireless operators competed prices to the lowest in the industrialized world. The same competitive forces are at play with regard to wireless data pricing, but could take hold faster and more intensely if more spectrum were put into the marketplace and regulators allowed secondary markets to work more quickly and effectively. Bravo to the FCC for making 30 MHz of WCS spectrum useable for supporting wireless broadband. More and faster decisions like that will go a long way to accelerating the downward price trajectory for LTE based wireless services.

As one can see in the table above, United States mobile operators are facing a significantly more constrained supply of spectrum suitable to support wireless data as compared to their foreign counterparts. When we normalize the spectrum available per person, the United States consumer is by far in the worst position. It has per person, only 1/3 of the spectrum available than Italy where demand for wireless data is comparatively weak. Other countries have assigned three to eight times as much spectrum per person to satisfy the demand for data. Consider the impact on service prices if the FCC really opened up the spectrum spigot. When spectrum was still plentiful in the United States, the wireless operators competed prices to the lowest in the industrialized world. The same competitive forces are at play with regard to wireless data pricing, but could take hold faster and more intensely if more spectrum were put into the marketplace and regulators allowed secondary markets to work more quickly and effectively. Bravo to the FCC for making 30 MHz of WCS spectrum useable for supporting wireless broadband. More and faster decisions like that will go a long way to accelerating the downward price trajectory for LTE based wireless services.