In case you are just tuning in, Verizon has been going through a rough time for about two years now. In fall 2021, it replaced Ronan Dunne as CEO of Verizon’s Consumer Group (VCG) as it struggled before filling the position with Manon Brouillette. It would be difficult to say that things have improved.

We live in peculiar times. For a long time, financial analysts wanted to convince us that when a mobile network operator (MNO) has a larger size than its competitors, the size advantage gives them a substantial edge in the market. Now, other financial analysts want to convince us that Verizon, because it is the largest provider in the market, is destined to lose customers for the foreseeable future. I disagree with both positions but would point to having a good plan, the ability to rapidly adapt to new circumstances, and superior execution to being the only sustainable competitive advantage in the market.

Verizon has traditionally differentiated itself as the premium provider in the market based on superior network performance. Taking network leadership to heart, Verizon charged ahead in 2G, 3G and 4G and created the fastest and largest network for at least the first three to four years of what is generally a seven-year technology era. The shock and awe of the early, rapid build created a nimbus of permanent network superiority even though, at least in urban markets, by year five, we had network parity. In contrast, in rural markets the network superiority persisted.

For the last decade, Verizon has internally fretted about what it should do if and when this trick would no longer work and its network superiority nimbus would be diminished, or even worse, large swaths of customers would perceive network parity or, even worse, someone else to have the better network.

Several poor decisions and outcomes around spectrum auctions weakened the strong network foundation. Verizon seems to have then tried to replace the internal differentiation of being the provider of the undisputedly best network with having the best streaming bundle and differentiating around that.

Replacing an internally generated differentiation with an externally acquired differentiation, especially when it is so easily replicable, is a dangerous gamble. To make this decision even more puzzling, Verizon engaged in the content-differentiation strategy at the same time when AT&T exited the content bundling with wireless.

AT&T and T-Mobile having seen the 2G, 3G and 4G outcomes decided they didn’t want to live through the same experience with 5G and put a lot more emphasis on network performance. While in Recon Analytics Data weekly net promoter score data, Verizon still leads in the network performance categories, the gap has undoubtedly diminished. Metered speed tests show Verizon being behind, but how much does it matter? In our purchase decision factor ranking, speed is a solid second out of nine metrics.

Especially T-Mobile, powered by Sprint’s spectrum and a greater network focus with various firsts has given Verizon’s network team a run for its money. AT&T has been more judicious in spectrum expenditures and build-out pace betting that speed test results alone don’t win customers and aligning its build-out more with customer and technical capabilities and usage. The slower build-out has not hurt AT&T’s success in the marketplace because it was able to execute on other purchase factors that existing and prospective customers find important.

Verizon’s recent promotion

On May 22, 2022, Verizon launched an online promotion where single-line customers would get $15 off, two-line customers $12.50 per line off, and three-line customers got $5 per line off. Since Verizon did not issue a press release around it, it was largely unreported.

We took it as an opportunity to test Verizon’s value proposition of all plans – 5G Start, 5G Play More, 5G Do More, and 5G Get More – against what the customers of the other providers, ranging from T-Mobile and AT&T to Google Fi and Mint Mobile, were willing to pay for the different plans for a different number of lines. This gave our clients one week later a read if they should worry, to what degree, and about what part of Verizon’s promotion they should be worried about.

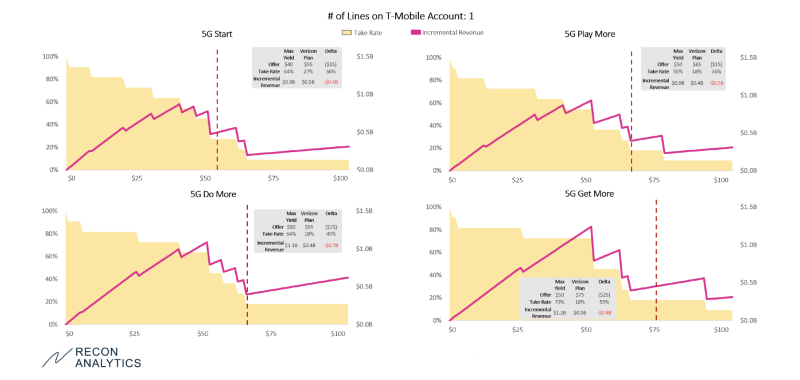

Below is how just T-Mobile customers were viewing Verizon’s single-line plans and for what price they would switch to the plan. While this is no sophisticated conjoint pricing analysis, it nevertheless gives some interesting insights. It also does not consider larger long-term pricing strategies that a company like Verizon would have to consider when making pricing decisions. The yellow shading represents the take rate at a given price point, while the magenta line represents the revenue that would be realized.

With the promotion, Verizon charged for a single line $55 for 5G Start, $65 for 5G Play More, or 5G Do More, and $75 for 5G Get More. As a reference point, Verizon just launched Welcome Unlimited for $65 for a single line for a skinnier offer than 5G Start.

T-Mobile customers’ highest revenue price point was $40 with a 64% take rate for 5G Start vis-à-vis Verizon’s $55 promotion. 5G Play More and 5G Do More were valued at $50 with 55% and 64% take rates respectively while Verizon was charging $65. Verizon 5G Get More plan discounted to $75 during the promotion was also valued at $50 with a 73% take rate.

Analyzing the data as in the above example vis-à-vis T-Mobile, it became apparent that in the one-line segment, the Verizon promotion would not save Verizon’s quarter. The numbers for the other providers for single-line customers were roughly similar to those of T-Mobile customers.

Interestingly, despite being the least generous, the three-line offer was the most competitive for several of Verizon’s offers. This brings us back to Verizon’s new Welcome Unlimited plan. It looks like a significant uphill battle to convince single-line customers to spend $65 per month when only two months ago, at least T-Mobile customers thought it was only $40 worth.

As I mentioned before, customers of different mobile service providers and for different line counts value Verizon’s plans differently, but in the one- and two-line part of the market a similar picture emerged.

Verizon isn’t suffering from a large size that dooms its progress; it suffers from a value positioning, value perception, and long-term pricing strategy issue.