The following Note is the first of a two-part series assessing some of last year’s key market developments and projecting their impact into 2014. We also offer our thoughts on the challenges and opportunities for wireless carriers this year and consider how competition will unfold in the months ahead. Part Two will look at what the year ahead may hold for devices, networks and spectrum.

Looking back, 2013 was a year of transformation in which several major transactions enabled the carriers to reshape and reinforce themselves for a Final Four competition for leadership in the U.S. market. Looking ahead, 2014 shapes up as a year of intensified competition in which carriers test a host of new options for relations with their customers and also step up a fierce contest to establish the superiority of their LTE network. Already, just weeks into the new year, AT&T and T-Mobile have raised and counter-raised with competing offers of cash to convince customers to ditch their current carrier and switch. And, Sprint has revised its plan for accelerated handset upgrades and launched a new Framilies plan to let larger numbers of customers come together and qualify for lower group rates.

Hanging over this continuing tussle to attract and retain customers is a parallel battle over the terms of the 2015 spectrum auctions as well as renewed speculation about a possible merger of a revitalized T-Mobile and spectrum-rich Sprint. The potential entry of DISH and the fate of LightSquared are wildcards that have the potential to reshape the current wireless market depending on how the two companies decide to proceed. The pre-paid market, roiled in 2013 by forced deactivations because of questionable Lifeline signups, bears watching as well. We expect Tracfone will help lead this segment back up in 2014.

As we gaze through the crystal ball, we see a landscape greatly altered from 12 months before. Repositioned as the snarky “uncarrier”, T-Mobile has pushed the market in new directions by decoupling the handset and service components of customer contracts. It also has repeatedly compelled competitors to respond to its redesigned service plans with new offerings of their own. As we open 2014, T-Mobile, Verizon, and AT&T are in the market with plans that could signal the beginning of the end for the handset subsidies that have fueled consumers’ enthusiasm for high-end, but pricey smartphones.

Among the open questions for 2014 is whether consumers would rather pay full price for their handsets, likely financed over time, in exchange for lower monthly service costs or do they prefer the longstanding subsidy model. We wait to see the degree to which each carrier will work to move consumers to a financing-model.

Changed Landscape

As it is, the restructured T-Mobile and Sprint are strategically better positioned than a year ago. After their own talks about a possible merger flamed out to start 2013, the two companies found other partners. T-Mobile struck first in a “reverse acquisition” of Metro PCS. The transaction shifted 9 million Metro PCS customers to T-Mobile, providing an immediate boost in revenues, and also bolstered T-Mobile’s company’s spectrum inventory. The reverse acquisition mechanism, which enables a previously private company (T-Mobile, in this case) to quickly list its stock on public exchanges by acquiring a publicly-held company, also created new financial flexibility and liquidity for T-Mobile and its parent, Deutsche Telekom.

Bolstered by new assets and under the in-your-face leadership style of CEO John Legere, the company shook up the competitive landscape with a host of new offerings and recorded substantial gains in customers. The company’s image has been transformed into that of a feisty and effective challenger, the brand looks fresh, and Mr. Legere has a knack for grabbing headlines. The company has now launched four iterations of “uncarrier” to continually stoke new enthusiasm. The solid investment in its network as well as the media spot light has brought T-Mobile back into consideration for a growing number of consumers. T-Mobile will continue to play the “uncarrier” tune until it no longer works; the difficulty will be to keep finding things that upset consumers and can be profitably recast by T-Mobile.

Sprint also moved in a new direction, ceding its independent status by selling a majority stake to Softbank to get the financial backing it needed to build out of its LTE network. Bankrolled by Softbank, Sprint added to its spectrum holdings by winning a bidding war against Charlie Ergen and DISH Network and acquiring the half of Clearwire it did not already own. With the two moves, Sprint eliminated the ongoing distraction of dealing with an independent Clearwire and emerged a spectrum powerhouse with twice as much spectrum as any other carrier. Toward the end of the year, Sprint acquired yet more spectrum by buying licenses from Revol Wireless, which closed up shop on January 16, 2014. Sprint has since targeted Revol’s customers with special offers from its prepaid brand Boost Mobile. Tactically, however, Sprint is in a difficult situation as its Network Vision project is woefully behind schedule and network quality has suffered.

AT&T and Verizon also moved to shore up their competitive positions. AT&T snapped up Leap Wireless, which sells the Cricket Brand, for $1.2 billion to add key spectrum and expand its position in the prepaid, non-contract market niche. After ten years of on-and-off talks with Vodafone, Verizon spent $130 billion to buy out the British company’s 45 percent share in Verizon Wireless and capture the efficiencies from running its wireline and wireless businesses as an integrated company in which strategies are set solely by Verizon management.

Tracfone also beefed up last year, acquiring a number of prepaid carriers in a market niche troubled by some overzealous carriers’ abuse of the Lifeline program. The acquisitions should pay off for Tracfone this year as it digests last year’s feast.

2014 should see fewer transactions – the opportunities simply do not exist for a repeat of last year. But one big deal is possible as Sprint continues to eye T-Mobile and news reports indicate it has lined up bank financing just in case. However, regulatory approval would not be a sure thing. Both the FCC and the Justice Department have previously suggested a desire for four or more national competitors in the marketplace and the resurgence of T-Mobile as a market driver –as DOJ hoped in opposing the AT&T/T-Mobile transaction in 2011 – would seem to raise an additional barrier to approval. Also, given the recent performance of the two companies, the issue of leadership could complicate talks. It’s possible that Softbank might prefer Legere over current Sprint CEO Dan Hesse to lead a combined company.

Competition Intensifying

The story for last year was T-Mobile’s customer gains after years of net losses. This year, we wait to see whether T-Mobile can maintain its momentum and if Sprint can begin adding to its customer list. Also worth watching is whether Verizon can retain its reputation for having the “best” network, a claim that is increasingly challenged and coveted by all three of its national rivals.

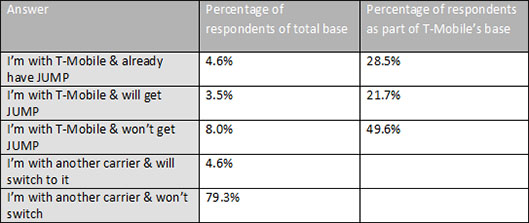

T-Mobile, which got a boost from finally adding the iPhone to its inventory, was the clear 2013 leader in offering new options to consumers. The initial uncarrier program cut monthly charges by $20 and introduced handset financing. The company also shifted most of its customers from service contracts to handset financing contracts that ties them to the carrier until they have paid off the handset, a clever switch that is the virtual equivalent of an early termination fee – but without the complaints. T-Mobile followed with JUMP!, which combines a rapid device trade-in and upgrade plan with traditional handset insurance for a lower rate. A few months later, it added free low-speed international data and texting plus lower-cost international roaming. This rapid-fire innovative pace forced its competitors into catch-up mode, trying to match many of T-Mobile’s innovations. Current indications are that T-Mobile should continue to grow for at least the next six months even without any new uncarrier announcements.

AT&T took aim at T-Mobile and Verizon by lowering its monthly recurring charge by $15 for customers who finance their device, own it outright, or who have had it for more than two years while on contract. Traditionally, AT&T has priced at parity with Verizon Wireless, but the new program drops its prices below Verizon’s for longer-tenured customers and should inhibit churn. The initiative also reduced the price differential with T-Mobile for customers who are not bound by a device financing or service contract. AT&T’s reduction for out-of-contract customers is its best idea so far for keeping its vulnerable feature phone base with the company. It should have help improve their feature phone retention rate, but we doubt it will entirely close that seeping wound.

Though tarnished by a number of large-scale outages of its 4G LTE service, the strength of Verizon’s network has helped it remain the fastest growing contract carrier as the Verizon halo of best network is still intact in the consumer’s mind. Network strength is Verizon’s most significant differentiator and retaining the lead in consumer perceptions about its reliability is vital to its growth strategy. But some metrics suggest the advantage has been slipping.

Recent data from RootMetrics, for example, suggests that AT&T’s LTE is faster than Verizon’s in a majority of markets. The company says, however, that Verizon still has an edge on reliability. When combining those two elements, RootMetrics’ gives AT&T the edge for “combined performance.” The fight for network bragging rights is likely to grow fiercer still as Sprint begins to roll out its super-speed Sprint Spark service. For its part, T-Mobile claims to be the top speed provider in half of its 20 LTE markets based on findings from Speedtest.net and has dramatically expanded its 4G LTE network to cover more than 200 million customers, surpassing Sprint. In the end, the consumers cannot help but be confused by all the contradictory claims.

The increasing capabilities of LTE networks also raises the possibility that one or more wireless providers might aggressively turn to current wireline users as a growth area and pitch them to switch to wireless for all of their broadband needs. AT&T has already announced such a vision and Verizon executives have publically contemplated it. Sprint has more than enough spectrum to make such a pitch and T-Mobile’s recent purchase of 700 MHz spectrum from Verizon brings wireline customers within its reach as well.

AT&T meanwhile must cope with weaker contract growth for handsets, perhaps by building on gains it recorded in tablets last year. During 2013, the company successfully upsold its existing customer base with additional devices. The company also entered the home security and automation business with Digital Life in a significantly more comprehensive and expansive way than any other company. The home security market is notoriously tough to enter due to the difficult approval process in every market it is offered. The company launched 57 markets in 2013 and started doing nationwide broadcast television, setting itself up for growth in 2014.

Sprint spent 2013 in almost perpetual turmoil – making its deal with Softbank, fighting DISH for Clearwire, shutting down its iDEN network and feeding other carrier’s subscriber counts. Network Vision has slowly turned into a nightmare with slow implementation and service degradation, which in turn has led to a reversal in customer opinions of Sprint and contributed to subscriber losses. These losses will continue at least through the remainder of 2014. While Softbank is now on the hunt for T-Mobile and is eager to purchase its smaller rival, it is unlikely that this pursuit will bring Softbank the salvation it apparently is looking for. The odds of winning an approval of such a merger are slim under the current administration, which views the revival of T-Mobile as one of its crowning achievements in promoting wireless competition.

In our view, Sprint might be better advised to get its own house in working order after last year’s tumult and put off a run at T-Mobile for a few years. Longer term, Sprint is pouring Softbank’s money into an upgrade of its LTE network with the intention of overtaking its rivals by 2015 or sooner and touting the newly-claimed technological edge to attract customers. If it can convert that plan to reality, Sprint would be better positioned for a future transaction as the power of two effective challengers combined would have greater upside than a slow mover trying to buy its way to better performance.

On the pre-paid front we see strong growth this year, led by an enlarged Tracfone. The segment started strong in 2013, outpacing post-paid by 10-1 in the early part of the year. But those too-good-to-be-true numbers were inflated by excessive Lifeline signups that the FCC later rolled back. In the end, prepaid net adds went negative as forcible deactivations were higher than adds and contract lines grew again.

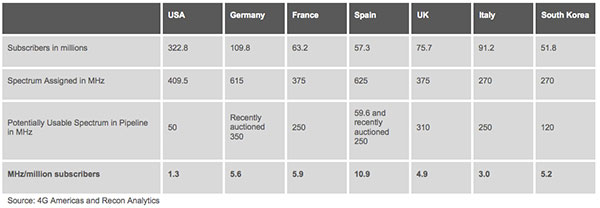

As one can see in the table above, United States mobile operators are facing a significantly more constrained supply of spectrum suitable to support wireless data as compared to their foreign counterparts. When we normalize the spectrum available per person, the United States consumer is by far in the worst position. It has per person, only 1/3 of the spectrum available than Italy where demand for wireless data is comparatively weak. Other countries have assigned three to eight times as much spectrum per person to satisfy the demand for data. Consider the impact on service prices if the FCC really opened up the spectrum spigot. When spectrum was still plentiful in the United States, the wireless operators competed prices to the lowest in the industrialized world. The same competitive forces are at play with regard to wireless data pricing, but could take hold faster and more intensely if more spectrum were put into the marketplace and regulators allowed secondary markets to work more quickly and effectively. Bravo to the FCC for making 30 MHz of WCS spectrum useable for supporting wireless broadband. More and faster decisions like that will go a long way to accelerating the downward price trajectory for LTE based wireless services.

As one can see in the table above, United States mobile operators are facing a significantly more constrained supply of spectrum suitable to support wireless data as compared to their foreign counterparts. When we normalize the spectrum available per person, the United States consumer is by far in the worst position. It has per person, only 1/3 of the spectrum available than Italy where demand for wireless data is comparatively weak. Other countries have assigned three to eight times as much spectrum per person to satisfy the demand for data. Consider the impact on service prices if the FCC really opened up the spectrum spigot. When spectrum was still plentiful in the United States, the wireless operators competed prices to the lowest in the industrialized world. The same competitive forces are at play with regard to wireless data pricing, but could take hold faster and more intensely if more spectrum were put into the marketplace and regulators allowed secondary markets to work more quickly and effectively. Bravo to the FCC for making 30 MHz of WCS spectrum useable for supporting wireless broadband. More and faster decisions like that will go a long way to accelerating the downward price trajectory for LTE based wireless services.