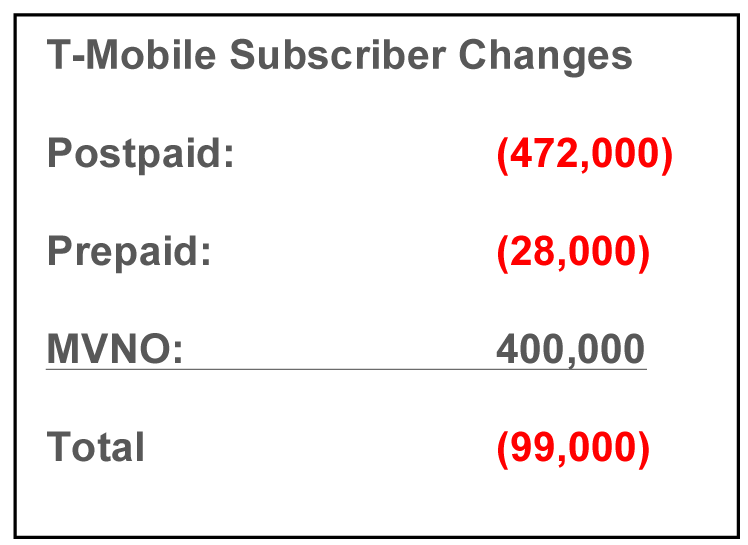

On May 6, 2011 T-Mobile USA released its quarterly results and it shows a carrier in distress. An improvement in APRU from $52 from $51 a year ago was the sole T-Mobile highlight of the quarter, but even that was offset by an increase in CCPU of $1. The company lost in aggregate 99,000 subscribers in the quarter.

On May 6, 2011 T-Mobile USA released its quarterly results and it shows a carrier in distress. An improvement in APRU from $52 from $51 a year ago was the sole T-Mobile highlight of the quarter, but even that was offset by an increase in CCPU of $1. The company lost in aggregate 99,000 subscribers in the quarter.

When the numbers are disaggregated the picture becomes even bleaker: The company reported that it lost 471,000 postpaid subscribers and that it gained 372,000 prepaid subscribers including MVNOs. The number of MVNO customers increased to 3.2 million in Q1 2011 while it reported in the Q4 2010 results that it had 2.8 million MVNO customers. This indicates that about 400,000 MVNO customers were added in the quarter resulting in a net loss of roughly 28,000 T-Mobile prepaid customers. This means that

T-Mobile lost subscribers in both own-label segements, postpaid and prepaid, and the only segment that is growing comes from partners not using the T-Mobile brand, namely Tracfone’s Safelink offer that markets to Americans on government assistance.

Due to the sins of the past (explained below) T-Mobile is melting at both ends of the subscriber spectrum. It is losing premium subscribers to Verizon and AT&T, it is losing value conscious subscribers to Sprint, and budget conscious subscribers to the disruptive unlimited providers such as Metro PCS, Leap Wireless, and Tracfone’s StraightTalk products. The only segment that seems to be growing at T-Mobile’s own brand product portfolio are the data-heavy unlimited offers, but even there is a price to pay as indicated by the increase in CCPU from $24 to $25 which offset the APRU increase. It raises the question: Where would T-Mobile be in five years from now without the AT&T merger?

While the company could survive the current storm, it could only do so through superior leadership, consistent and differentiated positioning, and the strong support from its parent. In the wireless market, everything happens with a significant lag period: It takes year one to change the fundamentals, it takes year two to change the perception of its own customers, it takes year three to change the perception of non-customers, and the results only change in year four – and that’s if you do everything right. At the beginning of the year, T-Mobile was the last of the nationwide wireless operators to make the regions directly responsible for the business results. Before that everything was controlled from its headquarters. While the move is laudable, one has to wonder what took T-Mobile so long? One of the factors that made Verizon Wireless such a machine in the early 2000s was Denny Strigl’s and Lowell McAdam’s decision to drive authority and responsibility to the regions. After Stan Sigman and Ralph de la Vega took over the reins at Cingular, which was losing customers at the time, they instituted a similar approach with tremendous success. Sprint is doing well with a similar approach of devolving responsibility at a regional level.

T-Mobile USA is in the current position because it was several years late launching a 3G network due to a lack of funding from its German parent. Only in late 2009 and in 2010, as the financial metrics already started to deteriorate, did T-Mobile USA build and then launch an increasingly competitive 3G/4G network. With it the company changed marketing campaigns and corporate positioning again and again from a value approach with Catherine Zeta-Jones to a social approach with its Stick Together campaign, back to a brief Catherine Zeta-Jones revival campaign in 2009, focusing on just handsets after that T-Mobile declared that “kids are free” to the current Largest 4G campaign. Just reading it makes you dizzy and confused and consumers became disoriented regarding what T-Mobile really stood for.. The current campaign around “Largest 4G network” will have to be changed again when Verizon will have a larger 4G network that T-Mobile and the company has to go looking for a new differentiator again. Carriers are growing through consistent, believable differentiation not through constant change what they are standing for.

The Sprint example shows that you can overcome a lot of adversity, if there is commitment to endure a long and arduous path combined with good leadership. The US market is competitive and companies can come back from near death when they do things right. The problem is that T-Mobile USA’s parent Deutsche Telekom is not committed to the US market the same way its competitors are – and nobody can be forced to be committed to a market. Deutsche Telekom chose the easy and financially prudent path out: Sell the company rather than rebuild the company and go through a costly corporate rebuilding and repositioning. The agreement with AT&T came just in time.