5G fixed wireless access (FWA) is transforming how Americans are accessing the internet. In less than three years, 7.9 million customers signed up with FWA as their preferred internet solution. Recon Analytics interviewed more than 40,000 home internet customers in the first 12 weeks of the year and the results are clear: FWA customers are happier with their service than with service through any other technology. The only thing standing in the way of greater success is more capacity, which is why mobile operators are clamoring for more licensed full-power spectrum.

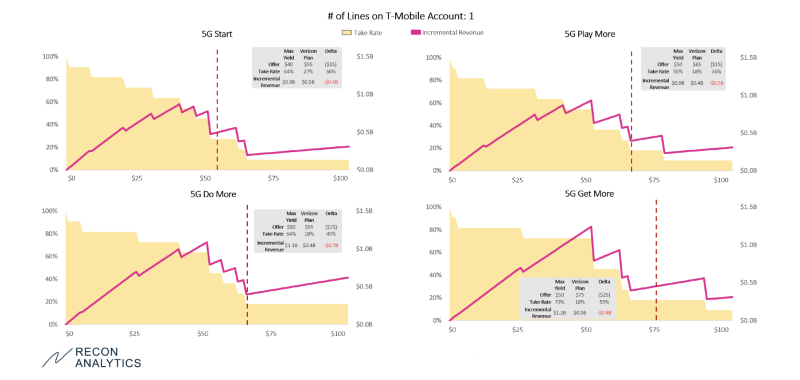

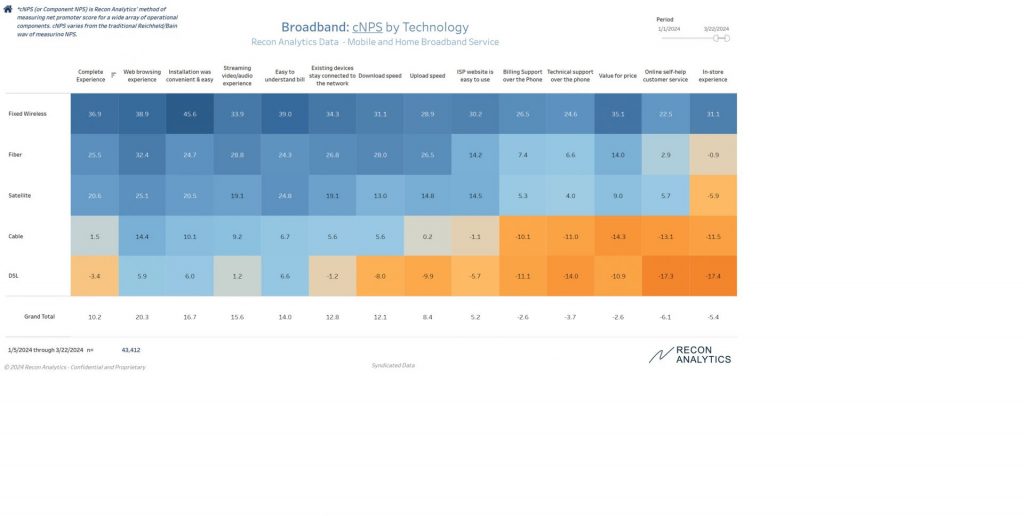

Chart 1:

FWA is the clear winner across the board

The ranking in Chart 1 makes sense, but is surprising at the same time. The mobile network operators built a very robust offering. FWA is not the fastest service, but under the current usage parameters it satisfies its customers not only on the traditional product side such as easy and convenient installation, a superior router experience, delivering an easy-to-understand bill, and online self-help customer service that people actually like, but also on the service side, ranging from the internet usage categories, to support over the phone and, most importantly, value for money.

It is important to keep in mind that there is a double bias going on with FWA customers. First, the vast majority of FWA customers have the same provider for their mobile service. Customers who are unhappy with their mobile service do not select the same provider and network for their home internet service. Second, there is a survivorship bias. Customers who sign up with FWA typically do this while they are still using a previous service with which they are unhappy. It is very easy and convenient to install and, if necessary, to return the FWA router and cancel the service, so prospective customers give it a try and take advantage of the cancellation poicy if it doesn’t work. We have a hard time finding customers who try the service and are unhappy with it, but have not returned it yet.

Customer service and connectivity

Chart 1 also reiterates what we have known for a long time: cable companies have poor customer service and need to improve. Telecom providers who are phasing out DSL networks and focusing on fiber provide substantially better customer service. What might surprise people is the strong performance of satellite service. This is mostly driven by Starlink, which is getting successively better over time, as a provider of last resort for many of its customers.

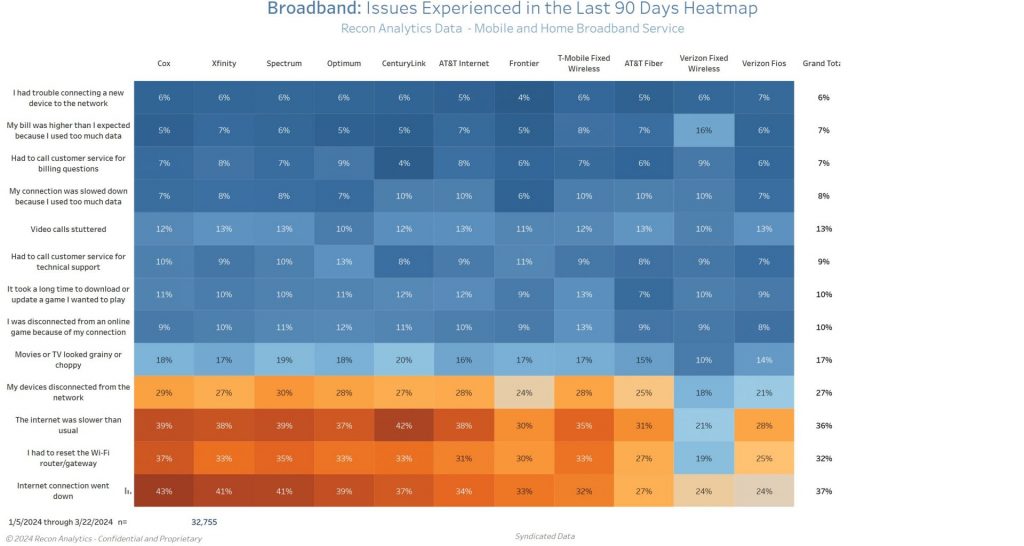

Recon Analytics also asks its home internet respondents every week what kind of issues they experienced with their internet connection. Chart 2 is ordered top to bottom with how often respondents experienced an outage. The most common issue, which was internet connection going down, is at the bottom. Furthermore, it is also ordered from left to right by how often they experienced their internet connection going down.

Chart 2:

As we can see in Chart 2, most of the issues are in one of two groups: internet connection going down or slowing down, and router issues forcing people to reset their router or having devices disconnect from the network.

Cable providers had the most issues in all four categories. Up to 43% of respondents reported that their internet connection has been interrupted, while fiber and FWA customers reported the least problems in this category. The newer, better routers provided by fiber and FWA providers also caused fewer problems compared to the routers from cable companies and DSL providers. One fiber and DSL provider told me that once they went away from sourcing the cheapest router to providing an excellent router, it was a game changer for them. The change reduced customer service calls and churn and improved customer satisfaction, more than offsetting the cost of the better router.

How to create more and better home internet choices

As of right now, the Congress and the FCC have created meaningful competition through up to three new providers with up to four brands in the markets where mobile network operators have been able to launch their service. It is incredible that even though we have seen network speeds for some providers decrease from 200 and more Mbps to low 100s Mbps, cNPS scores have not declined. MNOs still have enough capacity to provide their customers with sufficient bandwidth for what customers describe as a superior experience. Verizon and T-Mobile said that they have enough capacity for 5 and 7 million customers respectively with their initial FWA build. They are two thirds to that goal and will probably reach it by the end of 2024. After that, it will become more difficult and expensive to find the necessary capacity to compete with cable and DSL providers as vigorously as they do today. FWA is the fastest growing segment of the home internet market, while cable subscriptions are decreasing.

The government has three options, but the choice is pretty clear: It can spend $80 billion on various fiber incentive programs (BEAD, RDOF, etc) to bring another provider to markets where there is no provider offering more than 100 Mbps speed. It can take $80 billion from the wireless carriers for more spectrum (C-Band Auction for 240 MHz yielded $81 billion) and get three new broadband competitors in the form of FWA providers. Or, it can do both and create more and better home internet choices for Americans with a net zero cost.