Mobile Operating System (OS) providers like Google and Apple and device manufacturers like Samsung aren’t the only ones who can stick apps on the homepage of your mobile device. Others can too if the device manufacturer or OS provider plays ball. Some consumers find it helpful to have another app at their disposal, others call it bloatware and try to get rid of it as quickly as they can. At the beginning of May 2018, Verizon’s Oath business and Samsung announced a deal that will put Oath’s Newsroom app, Yahoo Sports, Yahoo Finance and Go90 mobile video apps preloaded on all Verizon flagship Samsung Galaxy S9 and S9+ phones. The deal also provides for native ads which blur the line between content and advertising on Oath’s apps and Samsung’s Galaxy app. In exchange, Verizon’s Oath and Samsung will share advertising revenues.

The Business Driver

With their partnership, Verizon and Samsung are attempting to raise their apps from the black hole that is typical app discovery to the forefront of the customer’s attention. This is similar to Verizon’s brandware program where it offers marketers to place their apps on Android smartphones sold in Verizon retail stores for somewhere between $1 and $2 per device. Why carriers and device manufacturers are pre-installing apps for subscribers is clear, even if their strategy is misguided: It’s additional revenues that are almost pure profit. Especially handset manufacturers are working with razor sharp margins. For app developers it is a much more difficult decision. They have to pay for the pre-loading if the customer uses the app or just deletes it.

The Problem: Ongoing Use and Uniqueness

Successful apps must conquer awareness, device installation, first use, and, finally, regular use. While preloading the Oath apps on Android certainly creates awareness of the app and forces device installation – it does little for first use and absolutely nothing to create sustained use.

More importantly, these apps are also not that unique. Pre-installing the same old types of apps people are familiar with, and likely have replacements for, is not going to help create sustained use. When we look at the different apps that Verizon is pre-downloading on the Galaxy S9 and S9+, it’s a decidedly mixed bag. The inclusion of Go90 in the lineup has been seen by critics as the proof point that all we have is bloatware. Rarely was an app more hyped and publicized than Go90, and rarely did an app flop harder. Yes, the other three apps Yahoo Finance, Yahoo Sports and Oath’s Newsroom are highly rated give access to top publishers and are popular without being preloaded, but it’s a stretch to say that they’re unique. Installing apps that aren’t unique result in what we’ve already seen in media coverage of this announcement: Bloatware.

Preloaded apps on Android smartphone leads you to two possible and not mutually exclusive possibilities: One is that the app discovery process is fundamentally broken and even great apps are not being found by consumers. Neither the Apple App Store nor Google play have an even half-way decent content discovery process. The other is that some app developers have a greater marketing budget than resources to develop a great app. Pushing suboptimal apps to unsuspecting customers is doubling down on a losing proposition. Instead of dying a silent death in obscurity, the apps and their developers get skewered by consumers and the press alike. Not all publicity is good publicity.

But “pre-installs” won’t be bloatware if they provide real value. Take Siri for example – no one complained about Siri being pre-installed. It was unique, cool, and better. No – not everyone uses Siri, but no one would argue that she wasn’t unique and cutting-edge when first pre-installed – and if you still don’t like it you can make it disappear in a folder. The route Samsung is taking with Bixby fits into this mold somewhat, but Bixby has a lot of kinks to work out before we can put it in the same class as Siri.

Better Matters

What continues to surprise me is that companies who have an impact on the customer experience are not trying different routes. If we really believe that better matters, why aren’t they pushing boundaries farther? The goal is to drive ongoing use and consumption of content on mobile devices, and do it in unique ways that consumers might value.

A quick review of what’s happening on Android Phones shows four unique solutions carriers and OEMs should investigate:

• Lock Screen Solutions replace default lock screen experience with content/ads (e.g., Unlockd, start by Celltick)

• Launchers permanently replace the default android user interface (e.g., Evie Labs, Aviate)

• Dynamic first screen solutions when there’s relevant content, make it available as the first thing seen AFTER unlock (e.g., Mobile Posse)

• Web Portals integrate content into the default homepage of mobile browsers (e.g., Synacor and Airfind)

It’s time for carriers to get aggressive and understand that the also-ran solutions like the Oath/Samsun aren’t going to excite consumers. Metrics do show that these alternate approaches have been well adopted by customer segments and, in many cases, drive greater usage. Being cautious and worried that an alternate approach will alienate users is holding them back from coming up with cutting edge solutions that still would work for a good segment of their subscriber bases. Not everything has to be a one size fits all solution – these innovative solutions can all be positioned as cool new tech subscribers can use if they like it. And if they don’t, that’s ok too – after all, some people don’t want to use Siri or Alexa either because of security concerns.

The Other Announcement

The other news in the announcement are mobile native ads. They do not stand out but are designed to fit into the regular content flow. The only difference between articles and the native ad is that the source is identified as “sponsored by” instead of just the source. They are much harder to distinguish from regular ads that are designed to stand out and with a catchy headline can get more click. The Mobile Marketing Association claims in its Mobile Native Ad Format document that native ads have higher engagement. Considering how new mobile native ads are relatively new, we don’t know how consumers will react when they click on a native ad when they thought they clicked on non-paid content.

Mobile Operating System (OS) providers like Google and Apple and device manufacturers like Samsung aren’t the only ones who can stick apps on the homepage of your mobile device. Others can too if the device manufacturer or OS provider plays ball. Some consumers find it helpful to have another app at their disposal, others call it bloatware and try to get rid of it as quickly as they can.

At the beginning of May 2018, Verizon’s Oath business and Samsung announced a deal that will put Oath’s Newsroom app, Yahoo Sports, Yahoo Finance and Go90 mobile video apps preloaded on all Verizon flagship Samsung Galaxy S9 and S9+ phones. The deal also provides for native ads which blur the line between content and advertising on Oath’s apps and Samsung’s Galaxy app. In exchange, Verizon’s Oath and Samsung will share advertising revenues.

The Business Driver

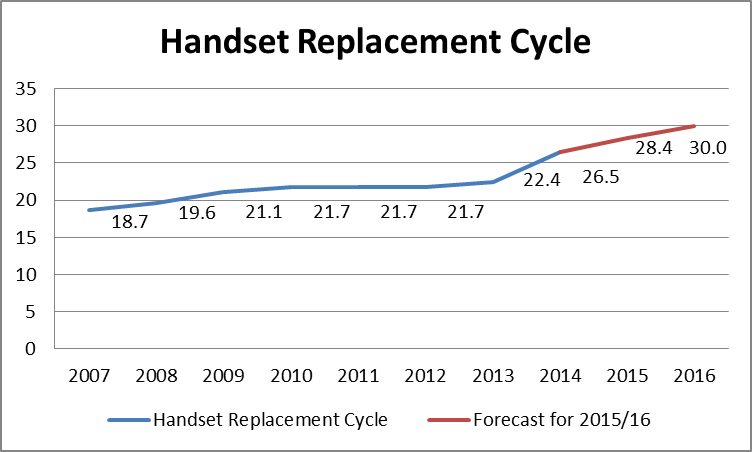

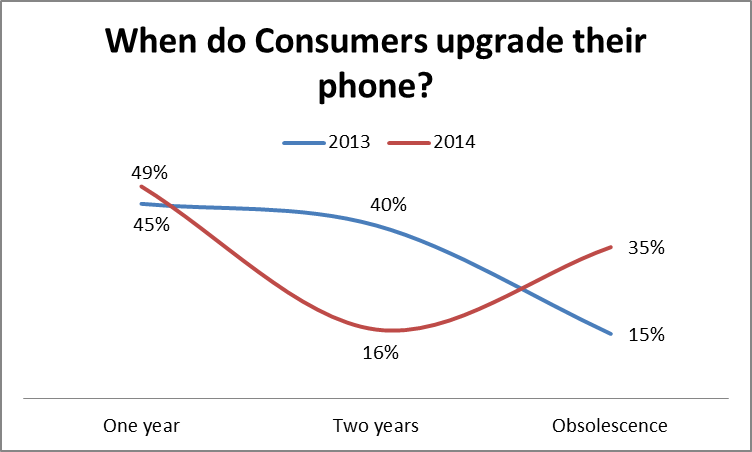

With their partnership, Verizon and Samsung are attempting to raise their apps from the black hole that is typical app discovery to the forefront of the customer’s attention. This is similar to Verizon’s brandware program where it offers marketers to place their apps on Android smartphones sold in Verizon retail stores for somewhere between $1 and $2 per device. Why carriers and device manufacturers are pre-installing apps for subscribers is clear, even if their strategy is misguided: It’s additional revenues that are almost pure profit. Especially handset manufacturers are working with razor sharp margins. For app developers it is a much more difficult decision. They have to pay for the pre-loading if the customer uses the app or just deletes it.

The Problem: Ongoing Use and Uniqueness

Successful apps must conquer awareness, device installation, first use, and, finally, regular use. While preloading the Oath apps on Android certainly creates awareness of the app and forces device installation – it does little for first use and absolutely nothing to create sustained use.

More importantly, these apps are also not that unique. Pre-installing the same old types of apps people are familiar with, and likely have replacements for, is not going to help create sustained use. When we look at the different apps that Verizon is pre-downloading on the Galaxy S9 and S9+, it’s a decidedly mixed bag. The inclusion of Go90 in the lineup has been seen by critics as the proof point that all we have is bloatware. Rarely was an app more hyped and publicized than Go90, and rarely did an app flop harder. Yes, the other three apps Yahoo Finance, Yahoo Sports and Oath’s Newsroom are highly rated give access to top publishers and are popular without being preloaded, but it’s a stretch to say that they’re unique. Installing apps that aren’t unique result in what we’ve already seen in media coverage of this announcement: Bloatware.

Preloaded apps on Android smartphone leads you to two possible and not mutually exclusive possibilities: One is that the app discovery process is fundamentally broken and even great apps are not being found by consumers. Neither the Apple App Store nor Google play have an even half-way decent content discovery process. The other is that some app developers have a greater marketing budget than resources to develop a great app. Pushing suboptimal apps to unsuspecting customers is doubling down on a losing proposition. Instead of dying a silent death in obscurity, the apps and their developers get skewered by consumers and the press alike. Not all publicity is good publicity.

But “pre-installs” won’t be bloatware if they provide real value. Take Siri for example – no one complained about Siri being pre-installed. It was unique, cool, and better. No – not everyone uses Siri, but no one would argue that she wasn’t unique and cutting-edge when first pre-installed – and if you still don’t like it you can make it disappear in a folder. The route Samsung is taking with Bixby fits into this mold somewhat, but Bixby has a lot of kinks to work out before we can put it in the same class as Siri.

Better Matters

What continues to surprise me is that companies who have an impact on the customer experience are not trying different routes. If we really believe that better matters, why aren’t they pushing boundaries farther? The goal is to drive ongoing use and consumption of content on mobile devices, and do it in unique ways that consumers might value.

A quick review of what’s happening on Android Phones shows four unique solutions carriers and OEMs should investigate:

• Lock Screen Solutions replace default lock screen experience with content/ads (e.g., Unlockd, start by Celltick)

• Launchers permanently replace the default android user interface (e.g., Evie Labs, Aviate)

• Dynamic first screen solutions when there’s relevant content, make it available as the first thing seen AFTER unlock (e.g., Mobile Posse)

• Web Portals integrate content into the default homepage of mobile browsers (e.g., Synacor and Airfind)

It’s time for carriers to get aggressive and understand that the also-ran solutions like the Oath/Samsun aren’t going to excite consumers. Metrics do show that these alternate approaches have been well adopted by customer segments and, in many cases, drive greater usage. Being cautious and worried that an alternate approach will alienate users is holding them back from coming up with cutting edge solutions that still would work for a good segment of their subscriber bases. Not everything has to be a one size fits all solution – these innovative solutions can all be positioned as cool new tech subscribers can use if they like it. And if they don’t, that’s ok too – after all, some people don’t want to use Siri or Alexa either because of security concerns.

The Other Announcement

The other news in the announcement are mobile native ads. They do not stand out but are designed to fit into the regular content flow. The only difference between articles and the native ad is that the source is identified as “sponsored by” instead of just the source. They are much harder to distinguish from regular ads that are designed to stand out and with a catchy headline can get more click. The Mobile Marketing Association claims in its Mobile Native Ad Format document that native ads have higher engagement. Considering how new mobile native ads are relatively new, we don’t know how consumers will react when they click on a native ad when they thought they clicked on non-paid content.